Readers are most likely familiar with typical American-Chinese dishes such as kung pao chicken, General Tso’s, fried rice, and dumplings. Now, authentic Chinese cuisine is so much more varied, nuanced, and exciting than what you’ll find at your favorite Chinese takeout place. Think about it—China has four times the population and is roughly 2,500 years older than the U.S. giving its cuisine ample talent and time to develop.

Traditionally, Chinese cuisine is broken into eight major regional cuisines (commonly referred to as the Eight Great Traditions): Cantonese, Sichuan, Shandong, and Jiangsu being the most popular and the rest being Anhui, Hunan, Zhejian, and Fujian. The biggest differentiator between the cuisines is the region’s geographic location and agriculture. For example, the humid, mountainous regions of Sichuan and Hunan are perfect for growing chilis and both these regional cuisines feature hot and spicy as the main taste profile. Alternatively, the Anhui and Fujian cuisines are well known for using wild herbs and game from their abundant forest land.

The following is meant to be a high-level beginner’s guide to each of the eight regional cuisines:

Cantonese

Cantonese culture originates from the Guangdong region. Its provincial capital, Guangzhou (otherwise known as Canton City), is a historic trading hub and therefore Cantonese cuisine benefits from many imported food and ingredients. Cantonese chefs aim to preserve and highlight the original flavor of the ingredients so they use few spices or sugar and favor cooking techniques such as steaming, stir-frying, and braising. In fact, most dishes simply combine fresh ingredients with garlic, ginger, and scallion (the “holy trinity”). This preference for mild and fresh taste springs from the fact that Guangdong region receives abundant rainfall, has a tropical climate, and is surrounded by lush farms and rice paddies providing the locals with access to a wide variety of fresh ingredients. An interesting quirk of Cantonese food is the chefs’ tendency to utilize every single part of the animal including offal, chicken feet, duck’s tongue, frog legs, snakes and snails. Typical Cantonese dishes include Dim Sum, Steamed Egg, Char Siu, Beef with Oyster Sauce and Steamed Chicken with Ginger Scallion Sauce. A local delicacy is shark fin’s soup.

Sichuan

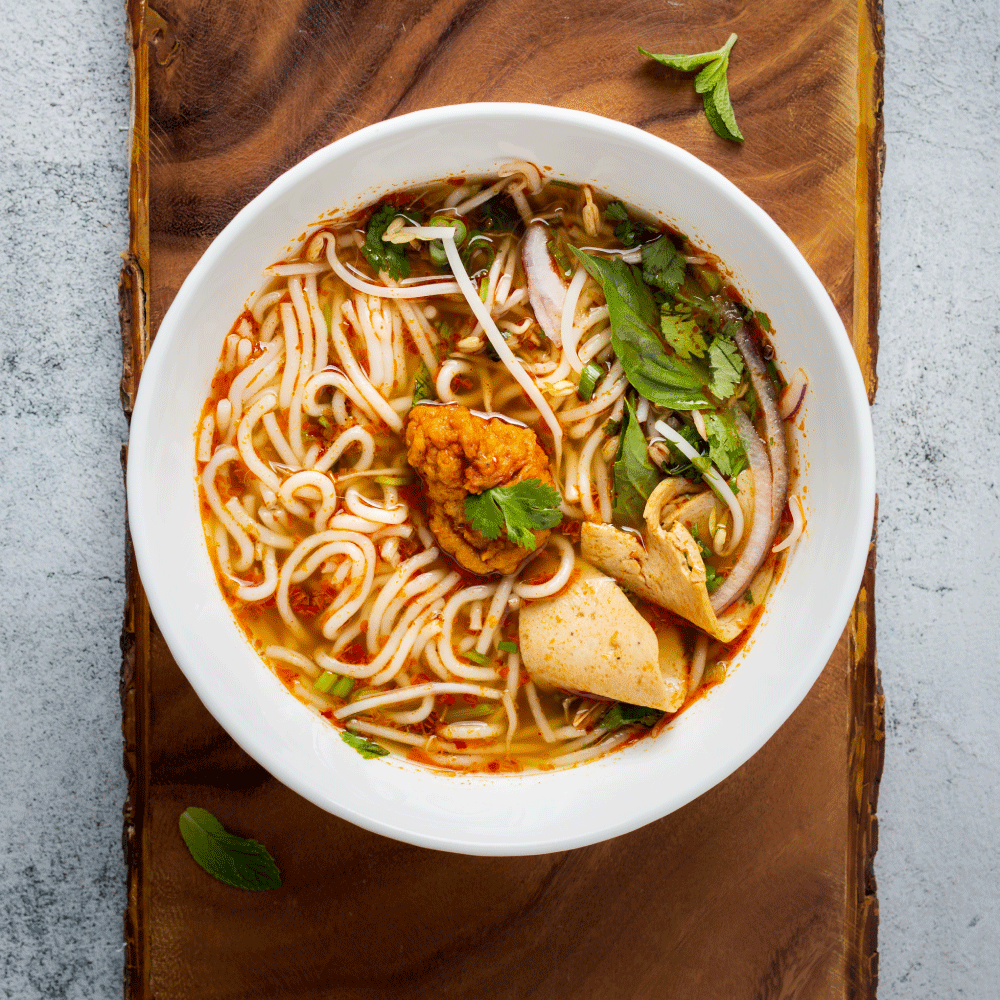

The Sichuan region is well known for its spicy dishes using the iconic Sichuan pepper. This pepper imparts a mala spiciness, characterized by a tingling-numbing feeling. However, chefs didn’t start using chili peppers until the 16th century when Portuguese traders introduced New World foods such as maize, potato, peanut, and…chili peppers. The Sichuan region is incredibly mountainous and humid; leading to a great growing environment for chili peppers as well as local’s desire to eat something that would cool them down. In addition to chili peppers and specifically the Sichuan pepper, local chefs heavily use fennel, pepper, aniseed, cinnamon, and clove. Pork is the most typical meat and beef is consumed more heavily when compared to the other regions of China due to the prevalence of oxen in the area. The cuisine doesn’t favor a specific cooking technique, instead the common pattern is the heavy use of chili oil and spice to impart as flavorful and spicy of a dish as possible. Typical Sichuan dishes include Mapo Tofu (my favorite!), Hot Pot, Dan Dan Noodles, Chongqing-Style Dry-Fried Chicken With Chilies, and Diced Chicken With Peanuts and Dried Chilies.

Hunan

The close-by Hunan region also heavily utilizes chili peppers in its cuisine. However, opposed to the Sichuan mala flavor stemming from the liberal use of chili oil—Hunan cuisine uses fresh peppers in its dishes resulting in a ganla (dry heat) flavor. In addition, many Hunan dishes have a distinctive sour-hot taste profile due to the popularity of vinegar as an ingredient and the abundance of citrus groves in the region. Hunan cuisine also uses smoked and cured goods in its cuisine more frequently than other cuisines. Typical Hunan dishes include Chairman Mao’s Red Braised Pork, Steamed Preserved Meat, Dong’an Chicken, and Chairman Mao’s Red Braised Pork.

The next four regions, Shandong, Jiangsu, Zhejian, and Fujian all lay on the coast and therefore heavily feature seafood in their cuisine.

Shandong

Shandong

The Shandong flavor is described as “salty, crispy, tender, and light.” Similar to Cantonese cuisine, the goal of Shandong chefs is to preserve the cut, color, and taste of the main ingredients. Therefore, the most popular cooking technique is “bao,” or extreme heat stir frying. Shandong chefs will heat up oil to an extremely high temperature in a wok and toss in their meat and vegetables. This quick fry locks in the flavor and keeps the oil from seeping into the food. They typically pour out the oil and add spices, herbs, and seasonings (typically a broth soup) and serve it hot. Other common cooking techniques are deep frying, roasting, and caramelizing. Shandong cuisine heavily uses condiments, especially vinegar, which is considered medicinal and often consumed by itself. Typical Shandong dishes include Dezhou Braised Chicken, Yellow River Fish, Intestines in Brown Sauce, and Sea Cucumber with Scallion.

Jiangsu

Jiangsu Region has the highest per capita income in China and their cuisine reflects the preferences of their wealthy patrons. Jiangsu chefs utilize high-quality and seasonal ingredients, advanced cooking techniques (no simple stir-frys in Jiangsu!), and elaborate presentation. For example, one of Jiangsu’s sub-cuisines, Huaiyang cuisine, is commonly used for government banquets and known for its “rainbow presentations.” The province has a wide diversity of agricultural products. In addition to being on the coast, there are also plentiful lakes and ponds providing lotus, Chinese water chestnuts, and water bamboo. Typical Jiangsu dishes include Lion’s Head Meatballs, Sweet and Sour Mandarin Fish, Nanjing Salted Duck, and Yangzhou Fried Rice.

Fujian

Fujian cuisine combines Jiangsu’s use of seafood and presentation with exotic delicacies from the mountains. Chefs are legendary for their cutting techniques—many Fujian dishes require slices as thin as paper and shreds as small as hairs. Garnishes tend to be fruit and vegetables cut into elaborate shapes such as blossoming flowers or graceful swans. Fujian cuisine is also well known for its “drunken” dishes marinated with red rice wine as well as its emphasis on soup stocks and bases used to flavor their dishes and stews. In fact, a common saying about Fujian food is “不汤不行” literally translated to “No soup is not OK.” Soup will often be the main or only beverage at a meal. Typical Fujian dishes include Drunken Ribs, Buddha Jumps Over the Wall, Fuzhou Fish Balls, and Sweet and Sour Litchis.

Zhejiang

Zhejiang cuisine uses similar ingredients as Jiangsu and Fujian cuisine but doesn’t focus on artistic presentation but rather on serving fresh food. The food is often served raw or almost raw and is fresh, crispy, and seasonal. Many folks have called Zhejiang cuisine similar to Japanese food because of its emphasis on freshness and simplicity. Chefs use bamboo shoots, ham, mushrooms, and green leafy vegetables to supplement fish and meat with almost no spice and light seasoning from Shaoxing rice wine, green onions, ginger, vinegar, and sugar. Typical Zhejiang dishes include Dongpo Pork, Sliced Lotus Root with Sweet Sauce, and West Lake Fish in Vinegar.

Anhui

Last but not least, Anhui cuisine is a little-known cuisine even with Chinese people. The Anhui region is mostly uncultivated forests and the locals mainly farmers. Therefore, its dishes are hearty peasant food, using wild herbs from the forests and simple cooking techniques of sauteing and stewing. Its cuisine is heavily associated with tofu as the Shou County (the “hometown of tofu” lies within the Anhui region. A regional specialty is stinky and hairy tofu. To make stinky tofu, chefs ferment fresh tofu in a brine from anywhere between a few weeks to a few months. There’s no standard formulation for the brine and its adapted to each chef’s preference and tradition, because of this stinky tofu can vary from golden to black can be eaten cold, steamed, stewed, grilled, barbecued, or deep-fried often accompanied by a sweet sauce or chili sauce and pickled vegetables. Most Chinese people like their stinky tofu as spicy as possible and as you can imagine, the taste and smell of stinky tofu is very intense. Hairy tofu is also fermented but in open-air and spoils until it grows hairs. Hairy tofu is never eaten raw but instead fried and coated in sauce. Other than stinky and hairy tofu, typical Anhui dishes include Stinky Mandarin Fish, Stewed Soft-Shelled Turtle with Ham, and Steamed Partridge.

China is a vast country with billions of people spread across a large geographic landscape, and you’ll find many more sub-cuisines and specialities within its borders than any article could possibly cover. However, hopefully this high-level introduction to authentic Chinese food has piqued your interest in the variety and diversity of “Chinese food.”

Helen works in the tech industry at “Silicon Hills” in sunny, weird Austin, Texas. She balances all that left-brain activity with freelance writing about the Texas restaurant scene and new food trends with a focus on Chinese cuisine. In her free time she renovates 1980s homes, films educational Youtube videos teaching analytics, and develops “no-code apps.” Instagram: @helen.w.xu

Helen works in the tech industry at “Silicon Hills” in sunny, weird Austin, Texas. She balances all that left-brain activity with freelance writing about the Texas restaurant scene and new food trends with a focus on Chinese cuisine. In her free time she renovates 1980s homes, films educational Youtube videos teaching analytics, and develops “no-code apps.” Instagram: @helen.w.xu